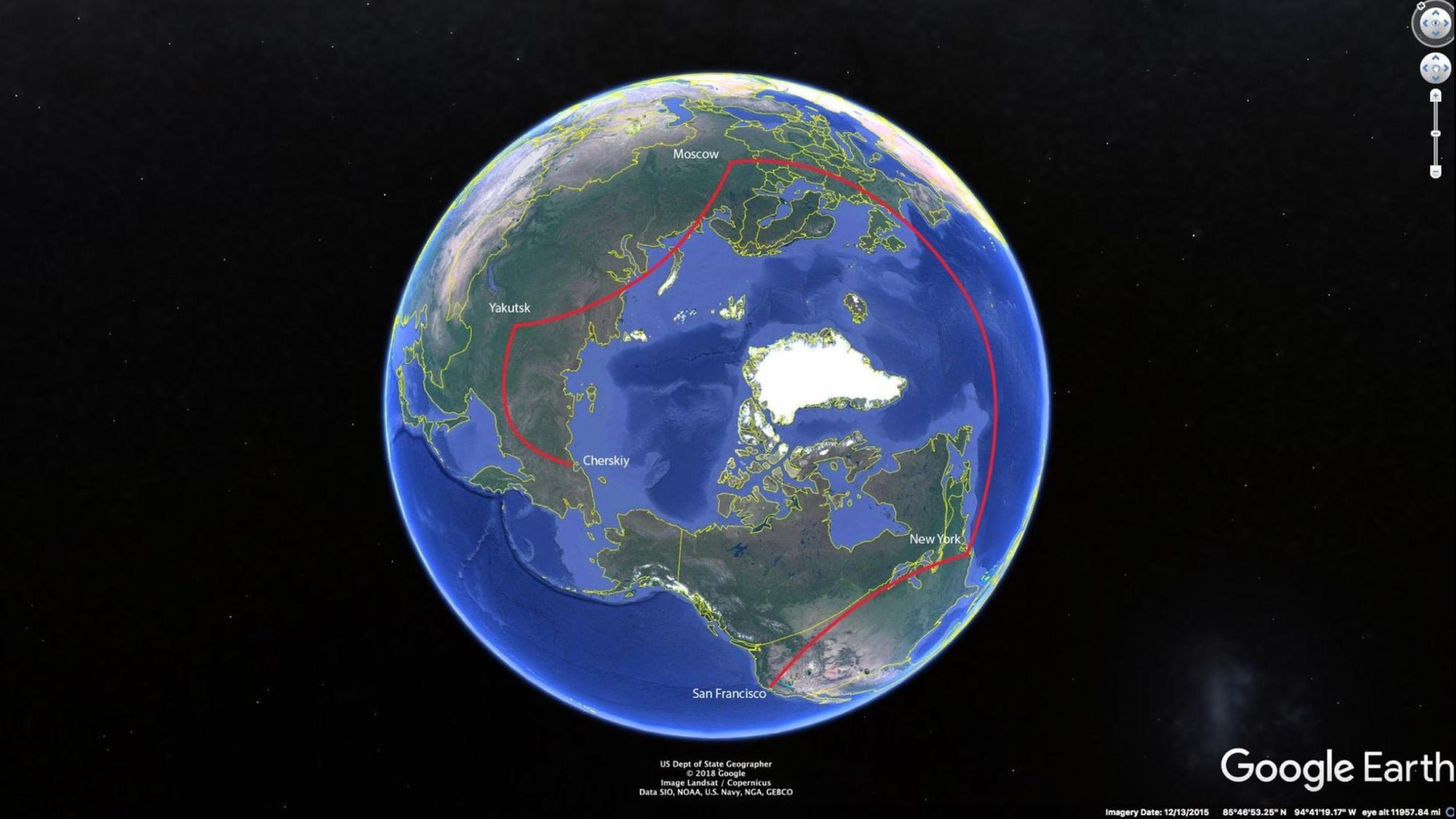

There will be three long flights across 15 time zones before I sleep in a bed, and we still won’t be there. Our destination is vastly closer to where we start than the path we have to take.

Under the auspices of the documentary being made about Long Now co-founder Stewart Brand by Structure Films, we are heading to Pleistocene Park in Siberia, where we will be filming Stewart and a team of scientists while they visit one of the first places on Earth that is being readied for the de-extinction and re-introduction of the woolly mammoth.

After driving to the San Francisco airport with Stewart, we met up with Long Now board member Kevin Kelly, check in baggage, and rendezvous with Jason Sussberg from the film team in the terminal. We immediately see our first flight is delayed an hour. That should be okay, given we had a planned three hours in New York to get to our next flight and have a longer layover in Moscow before departing for Yakutsk. We quickly learned, however, that the delay might stretch to five hours due to a storm in North East. Other members of our expedition already had their flights cancelled, and had to take a train and a car through the storm to JFK from Boston. We could feel the trip unraveling even before it began.

But moments later they updated us that the storm was moving out, and our flight would be boarding shortly. Hopefully this would be the only snafu in our long chain of travel. We made it to New York and began checking in for our next flight, where we got our first taste of Russian bureaucracy at the Aeroflot ticket counter. Even though we had sent our passports to the embassy a month before, and had all the visas affixed, it took at least 30 minutes of mysterious typing to check us in and give us horrible middle seats.

Twelve hours later, bleary-eyed and stumbling through the Moscow airport, we were finally able to meet up with the rest of the group. David Alvarado, the other half of Structure Films, Gerry Ohrstrom, the executive producer, and Brendan Hall, who would be operating the drones and still cameras, would round out the film team. On the science side was the eminent geneticist George Church from Harvard, who is doing the primary work on de-extincting the mammoth, as well as one of his post doctoral researchers Eriona Hysolli, who would be collecting mammoth tissue on this trip. Raja Dhir, a young biotech entrepreneur protege of Church focused on bacteria, and Anya Bernstein, a Moscow born Harvard professor of anthropology specializing in Russian futurism.

After a few hours of chatting and recharging devices we were back on an Aeroflot plane bound for Yakutsk, the capital of the Sakha Republic. Kevin Kelly pointed out the marked change in the people on this flight. While the people on our last flight had the fair complexions and chiseled features I normally associated with Russians, the people on this flight looked to have heritage from both Mongolian and Eskimo cultures. The vastness of Russia rolled by for hours under the plane. We traversed 6 time zones and had only crossed about two thirds of Russia. Our destination, the Sakha Republic or Yakutia, is an autonomous cultural region of Russia that is nearly the size of India and boasts the lowest temperatures ever recorded in the Northern hemisphere.

After landing I was stunned to see that the bags we checked in San Francisco with another airline actually rolled out of the conveyor… all except for one. Apparently the case with all the sound equipment had become separated from us at some point, and Aeroflot did not know where it was. This was a major setback for the filming team, as it was going to be very difficult for the equipment to catch up with us on the remainder of the trip — if it was ever found. Nonetheless, we headed out to our hotel, the Azimut Polar Star, which was complete with a stuffed Mammoth in the lobby, and had a delicious dinner of Georgian cuisine.

I woke up in dazed disbelief that we had to go to the airport yet again in the morning to board a plane for another 4 hour flight. On the Russian-made twin propeller plane we found they had removed many of the seats and replaced them with cargo bound for Cherskiy, our destination on the northern coast. Our group certainly stood out on this flight. As we flew north crossing the Arctic Circle and east across two more time zones, there was no sign of habitation. Almost everyone in Yakutia lives in a few major cities, leaving the 1.2 million square mile area — larger than Argentina — almost completely untouched. As we approached Cherskiy we could see the mighty Kolyma River beneath us, infamous as the region of the Russian Gulag labor camps in the 01930s-50s, and the watercourse we would be spending the next 10 days on.

The Top of the World

The moment the plane door opened after landing on the dirt strip, two Russian soldiers stepped in blocking our exit.

“Passports,” they said, just to our group.

We produced our documents.

“All with Zimov?”

We nodded.

They checked our names against a list and gave our passports back. After walking by scores of derelict planes, we met Nikita Zimov in the parking lot. With him was Luke Griswold-Tergis, a filmmaker who has spent the last 6 seasons with the Zimovs making a documentary about them and the Pleistocene Park. Generously, Luke was going to be able to loan the film crew some sound equipment while they hoped for their equipment to come in on the next flight — at best two days out.

The Cherskiy logistical hub was one of over a hundred polar outposts during the Soviet times. When the Soviet Union collapsed, so did the support and resources, leaving just a few places like this to scrape by. The 20,000 souls in Cherskiy at the height of the Cold War have dwindled to less than 2,000, and most of those are native people from local tribes. The city is replete with abandoned buildings and infrastructure, and if there were ever any paved streets, they are now long gone. We bounced through the two or three blocks that make up the town in a bit of a blur, and were taken down to the water just off one end of the air strip where a barge was waiting. Nikita was boisterous and cheerful, and rattled off facts about his hometown as we peppered him with questions. We loaded all the gear on to the barge and were joined by Nikita’s wife Nastia, two of their young daughters, and were soon underway on an amazingly warm and buggy evening up the river.

Sergey Zimov, Nikita’s father, arrived by speedboat after we loaded gear into the cozy bunk rooms. Pleistocene Park is Sergey’s brainchild, and he has been working on it with his family and a small staff for over 30 years. He has piercing eyes and kind of mythical presence that is both calming and demands your attention. Nikita explained that we would be cruising up river for about 20 hours to get to our destination, an eroding mud bank called Duvanii Yar (roughly translated to “windy cliff”) where we would search for mammoth bones. We sipped vodka and settled in for a long ride.

Almost every meal on board included moose meat. Lucky for us it was delicious, as were all of the meals. But we quickly learned the limitations of living above the Arctic Circle at a remote outpost. If it cannot survive 10 months of winter, grows in the ground, or won’t keep indefinitely, it is a delicacy that has to be flown in. Everything else comes by barge in the summer, or is hunted and foraged locally — like moose. There are a few greenhouses in town whose soil beds are heated by the local coal-fired steam plant, where a few precious vegetables can be grown during the months when there is light. Everything else has a cripplingly high cost of shipping. Something like a potato or chicken meat could be the most expensive thing on your plate.

The sun was nearly always setting, and would barely dip below the horizon from midnight to 3am. It made for gorgeous “golden hour” lighting, and our trip up-river was glassy and calm in a way I had never experienced on the water. Even understanding that a body of water this large could be a river seemed to defy my definition of the term. The Kolyma is one of the last major wild rivers in the world. While it has a few interventions at its headwaters, the vast majority of it is untouched by civilization, and here, where it meets the Siberian Sea, it is wide enough that you can barely see both shores.

Duvanii Yar

In the slowly developing dawn, the muddy cliff of Duvanii Yar emerged on our port side. From a distance it did not stand out in any way, but this place is famous in the world of mammoth hunters. A mammoth tusk sells for $40,000 and is the last legal source of wild ivory on the planet. Locals scour these shores after large storms, or when the water is lowest revealing new bones. The windfall of a mammoth tusk find is like winning the lottery.

We take small boats to the shore and Sergey explains that the water is too high to find much today, but reaches down by his feet amidst the driftwood and pulls up a bone proclaiming, “Buffalo, 35,000 years old.” We soon come to realize that we are standing in a place that used to be a wildly dense ecosystem. In Sergey’s Pleistocene Manifesto he writes:

During the ice age, Northern Siberia accumulated a thick layer of loess sediments. These are the soils of the mammoth steppe. By counting bones in these frozen sediments, it is possible to accurately estimate the density of animals in this ecosystem. On each square kilometer of pasture lived 1 mammoth, 5 bison, 8 horses, 15 reindeer. Additionally, more rare musk ox, elks, wooly rhinoceros, saiga, snow sheep, and moose were present. Wolves, cave lions and wolverines occupied the landscape as predators. In total, over 10 tons of animals lived on each square kilometer of pasture — hundreds of times higher than modern animal densities in the mossy northern landscape.

This immense density of life has stacked up in the permafrost layers at a scale that is hard to comprehend until you learn how to see the bones.

The difficulty in finding bones was not that there were so few, but that they were mixed with the driftwood that looked nearly identical. Every piece of worn wood looks like a bone at first. Those that have a reddish tint often are. One of my first finds was a 40,000 year-old jaw from some sort of grazer.

Once your eyes learn the subtle differences to look for, bones are everywhere. Over the course of the morning, scores of specimens were found: Lots of buffalo, deer and other more common pleistocene grazers, and even a few mammoth bones, including a nice large shoulder bone. I asked Sergey if bones were found in these densities everywhere, or if this place was some sort of graveyard that accumulated remains. “Like this everywhere, but here, the river digs them up for you.”

Another feature of this location that was exposed by the river erosion was the tundra itself, and the ice wedge structures that litter the underground landscape. Hiking up from the river through gorgeous wildflowers and swarming mosquitoes, you can look up at the natural ground level before it was cut by the river. I had heard about permafrost and understood it to be permanently frozen ground, but I had never understood that it was filled with varying structures like this. The dirty ice melting in front of us was tens of thousands of years old, and filled with smelly organic compounds and gases being released into the atmosphere.

The visit to Duvanii made the idea of the “mammoth steppe” extremely real. There was something elemental about being surrounded by Pleistocene bones in a melting tundra landscape. You could close your eyes and feel how rich this ecosystem was before it was hunted into extinction.

Our trip down river went faster as we traveled with the flow of the water. We stopped for the night at the tiny home of a few fishermen who live along the banks of one of the smaller tributaries. They brought dried fish aboard, and one of them turned out to be quite a singer, regaling us all with Russian folk songs. After each song, Nikita translated the plot of suffering and injustice. This guy was basically the Siberian Johnny Cash.

Returning to Cherskiy we lugged our gear up to the The North-East Scientific Station (NESS) run by the Zimovs as a kind of HQ, bunkhouse and science facility. We joined a group of Russian geologists who were there studying the tundra both in and around Pleistocene Park. The station itself is a repurposed TV Satellite dish facility left over from the Soviet era. The dish is no longer functional but it lends a bit of gravitas to the location and is easy to pick out as you approach from the land or river.

For the next week this would be our home base as we struck out for the Pleistocene Park, ice caves, and other scientific outposts. It turned out to be good timing to be returning to land. Our moment of warm Siberian summer was beginning to come to an end.

The Park

The next day we were heading to our primary destination — Pleistocene Park. We had been learning about the theory of the park over the last few days and it at least sounded simple: Bring the grazing species back to Siberia, clear the trees and brush so that the grasses could come back, expose the soil to the cold air, and increase its reflectance (albedo). This would help keep the tundra frozen, and all the greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane in the ground. One of the sticking points in scaling this plan, however, is the part where you clear the trees and brush over millions of square miles. The Zimovs can do it in the few square miles of the park, but not all of Siberia, much less Northern Europe, Alaska, Canada and Greenland. This is where the mammoth comes in. It is believed that mammoths would keep the small trees and brush in check, leaving the majority of the land as fertile grasses for grazing, and, most importantly for climate change, flat expanses for bright white fields of ice and snow reflecting sunlight.

Everyone bundled up for the one hour speedboat ride to the park. The little open aluminum boats were great workhorses on this trip, but for each excursion we made, at least one had an issue that required a bit of repair. The Zimovs and Luke fixed each problem deftly, and only once did a boat get stranded after dark, requiring someone to go back out for them.

Arriving at the park, we were met by two of the employees that live there year round in a house built on top of two shipping containers (the area floods and they have already had to go in and out of the second story windows a few times). Right at the headquarters we were able to see a baby moose they were nursing to release soon, a recently introduced herd of muskox, and a lone buffalo.

The buffalo was actually a developing story while we there. The Zimovs have been trying to import 10–20 more buffalo for months and have them all ready to go out of Alaska, but the air transport companies keep backing out at the last minute. Bringing animals in from around Russia is tricky due to the distances and lack of roads, but bringing wild animals from other countries is proving to be quite difficult logistically.

Nikita walked us around the park and showed us an area where they have cleared the scrub forest mechanically (with a bulldozer), as well as areas where they were draining some of the ponds into the river, leaving fertile grassy pastures. Both of these methods are being tested to generate the desired grasslands that the mammoths and grazers used to create and maintain. As we toured around, we were stalked by a few curious reindeer while we swatted at the mosquitos.

I should take a moment to talk about the bugs. On any day above freezing we were generally inundated by mosquitos. We were told that this was not bad, and that we “should have seen it a couple weeks ago.” Indeed none of our hosts even zipped up their bug shirts, but us visitors were covering as much of our bodies as possible with netting and DEET.

One thing that we all noticed about this area was the profound lack of birds in the air, or fish jumping in the water. I am not sure what the mosquitoes feed on when we are not there, but it was clear the fish were not preying on them. Perhaps it was just the time of year, or that behavior is just different, but I have never visited a wilderness as devoid of visible fish and birds as this place.

After a lunch in the cozy bunkhouse structure we got in the boats to go and see if we could find one of the herds of wild Yakutian horses that were in the park. We located them fairly quickly and I think they were one of the most majestic species that they have on the property. They let us get pretty close as they are clearly not afraid of humans.

We returned to the park headquarters for our last stop of the day — the ice cave. In this area it is normal to dig ice caves to act as a year round freezer. But at Pleistocene Park, researchers wanted a window into how the soils and ice wedge structures were fairing underground, and dug an elaborate multi-level set of tunnels that access hundreds of lateral feet and at least 50 feet down. They use these tunnels to study the ongoing effects of the changes on the surface as well as soil chemistry. After several hours in these caves standing on solid ice, we were ready to head back.

We got back in our boats to take a long cold ride in the rain back to Cherskiy. Again one of the boats broke down and had to be retrieved, but we all made it home safely. Every one of us walked away in awe of how much work is being done in this far corner of the world, as well as amazed to see what a shoestring budget it is being done with. This is possibly one of the most important climate experiments underway, and it is almost completely un-funded and unnoticed. We all agreed there should be experiments like this going on in multiple places and informing each other. The world does not just need one Pleistocene Park, it needs a network of parks in Alaska, Canada, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and across all of northern Russia.

Mammoth Tissue

Many more days were spent in and around Cherskiy, returning to the park, capturing methane from lakes, visiting scientific outposts, and an evening in the recently built Russian Banya (steam bath). But the final stop for the trip was a visit to the Mammoth Museum in Yukutsk on our way home. A few of us had ventured on ahead to spend a couple days in Moscow, but George Church and Eriona Hysolli were able to acquire some small tissue samples that would allow their work to continue in identifying the genetic differences between mammoths and modern Asian elephants.

Once these two genomes are properly compared, George Church and his lab hope to be able to use modern genetic techniques, and likely some yet to be invented gestation techniques, to be able to bring the mammoth back. The most obvious place for its reintroduction is a place like Pleistocene Park. Mammoths will hopefully once again be roaming the steppe, and keeping the tundra safely frozen, after being absent for nearly 10,000 years.

Learn More

- Head to Revive & Restore, Long Now’s de-extinction and genomics project.

- Read Ross Andersens’s 02017 cover story in The Atlantic on Pleistocene Park.

- Check out more photos by Brendan Hall, Kevin Kelly, and myself.